How many people are working?

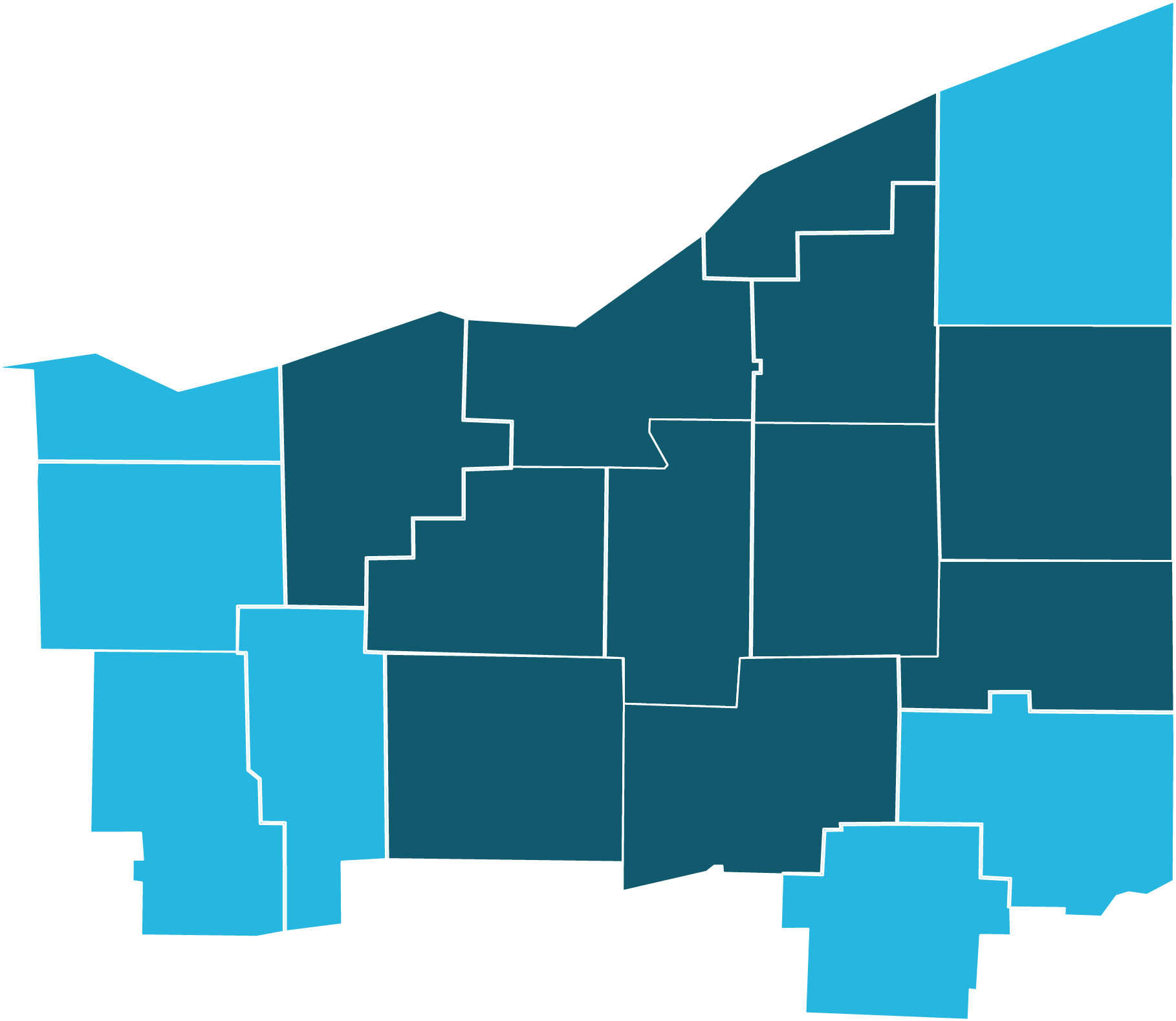

In 2021, there were 1,637,893 people in jobs in Northeast Ohio—95,510 fewer than in 2019, representing a 5% decline in the number of employed people since the start of the pandemic.**

%

The region has 5% fewer employed people than it did two years ago.

**Source: U.S. Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators Beginning of Quarter Employment: Counts (yearly averages), for 11-county region.

Where are the workers?

Quit a job in the past year*

Started freelance/Contract work since the pandemic began*

Out of the workforce because of Long Covid symptoms*

Retired in the past two years*

Retired earlier than expected in the past two years*

Where is the opportunity?

Retired recently, but considering a return*

Working part-time but want full-time work*

Out of the workforce but could be encouraged to look for work*

Need more training to get ahead*

Planning to quit this year*

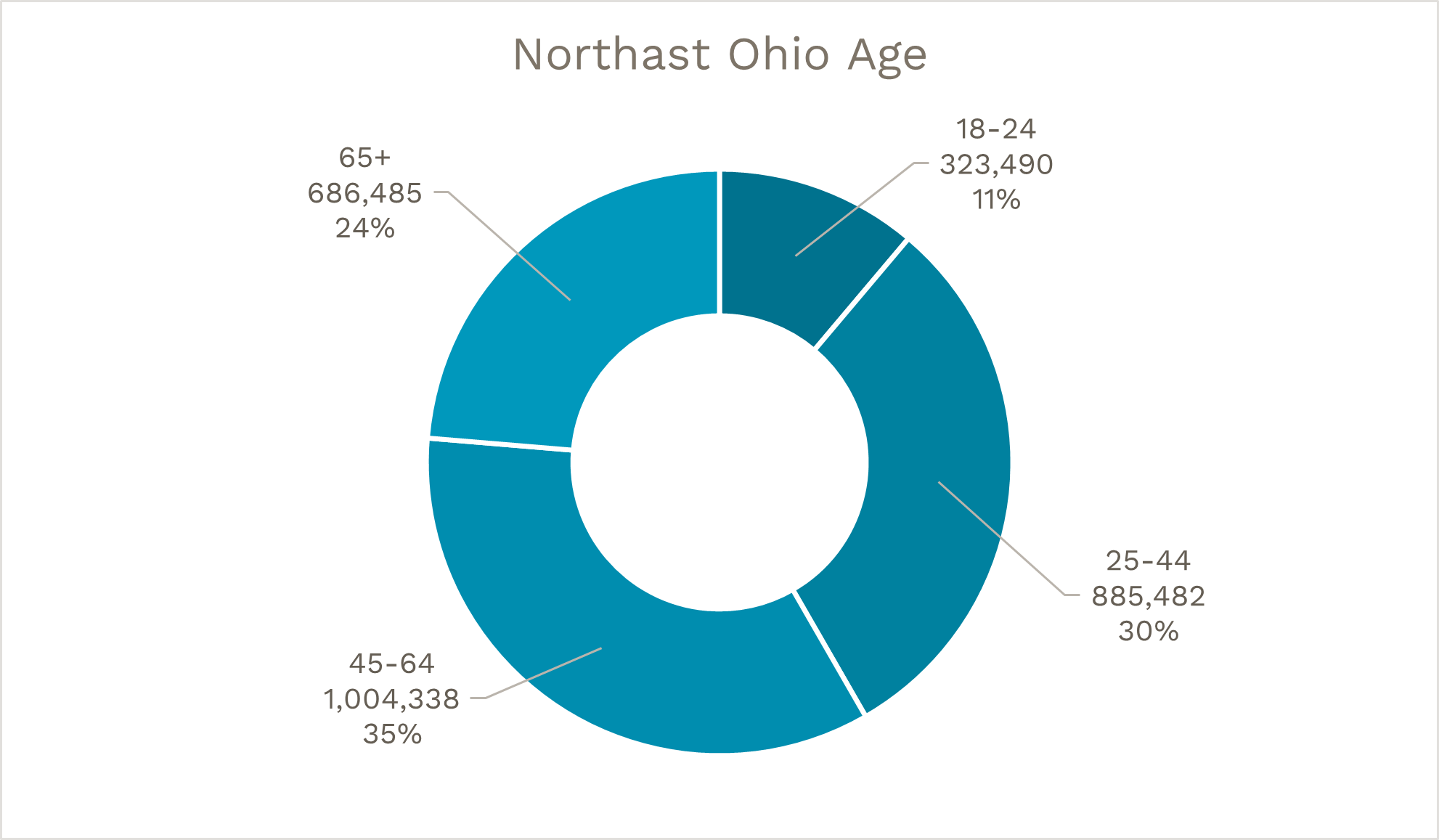

*Data from a statistically significant and demographically representative sampling of 5,000 adults across 11 counties in Northeast Ohio was extrapolated into estimated population impacts, based on a total number of 2,899,795 adults (18+) in the survey area.

Where Are the Workers?

With an estimated two jobs open for every one person looking for work,1 many are naturally asking, “Where are the workers?” Since the pandemic, theories abound about why workers are quitting, what they are doing to make money, and how they are spending their time. This section quantifies various factors influencing the tightness of the labor market and suggests where the greatest opportunities are to pull more workers in.

Northeast Ohio workers are either not in the workforce anymore—due to retirement, layoffs, sickness, death, or other reasons—or they are exercising choices: quitting, taking on contract or freelance work, changing careers. In many instances, people are dropping out of the workforce or making different choices because of dissatisfaction with their current options, health issues, or challenges related to transportation, childcare or other barriers that prevent them from finding or accessing what they need to excel in a job. Read on to learn more.

Not in the Workforce

There were an estimated 95,510 fewer people employed in Northeast Ohio in 2021 than in 2019.2 What happened to these workers?

They are not working and not looking for work.

There are roughly 343,484 working-age adults in Northeast Ohio who are not working and not looking for work (meaning they are out of the workforce and not included in unemployment numbers).

The main reasons people aren’t looking for work? They have a disability that prevents them from working, they are staying at home to care for children, or they have other medical or health issues. A very small percentage (4%) are actively choosing not to work.

A third of those currently out of the workforce—or about 115,698 people—said they could be encouraged to return, if the pay was good, if they could work from home or if they could find a good fit.

They retired, some earlier than expected.

The “silver tsunami,” talked about for more than a decade, is here. In the last two years, 125,090 people in Northeast Ohio retired—about 61% of those retired earlier than expected. (This is roughly in line with the rate—59%—of people retiring earlier than expected prior to the pandemic.)

Those who did retire earlier than expected in the last two years did not do so from a position of financial security; only 4.6% said they were financially able to do so. Those more likely to have left early include people with an annual income of less than $50,000, those with less than a high school diploma or with some college, and those with children at home. Their primary reasons for retiring early were poor health, a disability or injury, their company closed or they lost their job, or personal obligations.

Almost 30% of those who retired in the last two years—or roughly 36,229 people—said they plan to go back into the workforce. While some employers may find success attracting recent retirees, such a strategy isn’t forward-looking. Retirements largely are and will continue to be a reality of our changing population more than an impact of the pandemic.

They are still sick from COVID.

The impact of having contracted COVID is still preventing some people from actively participating in the workforce. About 102,130 people say the effects of long COVID affected their employment, with half of those saying it is still keeping them from finding or keeping a job.

They are permanently lost.

The toll of human loss from the pandemic is staggering. As of the compiling of this report, more than 15 million people across the globe had lost their lives from COVID. In the U.S., the death toll is more than 1 million. These were mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, daughters, sons, friends, co-workers. Their loss is felt by the people who loved them, and in many instances, by the businesses that relied on them. More than 9,000 working-age (18-64) adults in Ohio have died since the start of the pandemic.

Exercising Choices

The pandemic has left people feeling burned out, given them an opportunity to reevaluate work and—in this tight labor market—emboldened them to make different choices. What are people doing?

Quitting their jobs.

Take a minute and think of five people you know. It’s very likely at least one of those people quit their job in the last 12 months, and a one-in-two chance they didn’t have another job lined up when they quit. More than 400,000 people—or about 20% of the workforce—in Northeast Ohio quit their job in the last year. More than half of those didn’t have another job secured before quitting.

The “quits rate”—once an obscure economic indicator—became a dinner table topic overnight as the number of people leaving their jobs in the United States reached an all-time high of 3% in September 2021; higher than the average 1.97% over the course of the previous two decades. This is where the change in worker sentiment most clearly shows up. Indeed, worker attitudes coming out of the pandemic are vastly different than those during the last big economic shift caused by the financial crisis of 2008 and the resulting Great Recession. At that time, workers experienced deep instability and held on tight to their jobs; risk aversion was high. The quits rate in August 2009, for example, was a record low of 1.2%.

The reasons people are quitting vary. As one employer put it:

“Trying to describe why people are leaving is difficult. Everyone has a different story.”

But no matter the reason, the quits seem to have been triggered by an opportunity during the pandemic to pause and reflect. Though it was an open-ended question on the survey, a few reasons for quitting kept coming up—and most are indicative of workers being fed up with the status quo. More than half of those surveyed cited one of the following reasons for quitting: a negative work environment; low pay; in transition (e.g., moving, parental leave); schedule conflicts.

And people are going to keep quitting. An estimated 330,282 people plan to quit their job in the next 12 months. A vast majority who are planning to quit (83.4%) said they will look for another job. A little more than half (55.8% or 184,021 people) of those planning to quit said they could be convinced by their employer to stay, for the right incentives. (Note to readers: Every person retained is someone who doesn’t need to be hired. It’s worth checking in with employees to see how they’re feeling about their job before they go somewhere else.)

Working, but not at a traditional 9-to-5.

Taking on freelance or contract work.

Many people have expanded ways of earning money, especially in the last two years. An estimated 611,964 people, or about one in five adults, have done freelance or contract work, including app-based work like Uber, Door Dash or Instacart, or household tasks like yardwork or housecleaning, in the past 12 months to earn money. Those who are more likely to have done this type of work include part-time workers, males, residents ages 18-44, those with an annual income under $75,000, residents with a college degree, those currently enrolled in college, Black or multi-racial residents, and those with children in the home. More than two-thirds of freelance workers have only been doing this type of work for two years or less, and the majority (86%) indicated they enjoy this type of work. One in three people say they plan to start doing freelance or contract work in the next 12 months—and those more likely to do so are Black or multi-racial, very young (between 18-24), low-income (under $25,000/year), and parents of children under the age of five.

Working, at more than one job.

The pandemic drove more people to take on more than one job. One in five people, or an estimated 344,695 people, who are working in Northeast Ohio have more than one job, with the average number of jobs being just over two. Nearly half of those people only started working more than one job since the pandemic. Those who are more likely to have more than one job include freelance workers (see above), younger workers (between 18 and 44), single people, those with an annual income between $25,000 and $75,000, workers with some college or a graduate degree, those who are enrolled in college, Black or multi-racial workers, workers with children under five, and those with five or more people in their household.

Working, part-time, or wishing they were.

The appeal of part-time work is significant. Fifteen percent of workers, or about 438,728 people, are part-time, and more than half prefer it that way. Nearly one in three full-time workers wish they worked part-time. The top three reasons people give for doing part-time work: personal obligations (24.9%); being a student (15.2%); and personal choice (11.8%). This is consistent with what employers are experiencing: Many companies have said they’ve had an easier time hiring for part-time positions and are seeing more full-time people want to move to part-time work. Employers have an opportunity to evaluate their staffing needs and consider whether more part-time positions could fit into the overall picture.

Working, for themselves.

About 16% of Northeast Ohio workers, or 250,290 people, are self-employed. About half of those describe themselves as business owners, and about 45% identify as independent contractors or freelancers. A little more than a quarter of all self-employed people have paid employees. 243,948 people started a business or became self-employed during the pandemic, and another 471,447 people expect to start a business or become self-employed in the next 12 months. Those more likely to do so are Black or multi-racial, very young (18-24), low-income (under $25,000/year), and parents of young children.

Working, for someone else.

Of those who quit their jobs in the past 12 months, the majority (62.2%) landed somewhere else (whether they had a job lined up when they quit or not).

Re-imagining their careers.

About 454,672 people said the pandemic caused them to change their career plans. And workers are taking leaps and feeling good about their chances of landing on their feet. Of the 40% of employed people planning to look for another job in the next year, more than half (51.6%) said they plan to look in a different industry; 60% said they’d look for a different position.

And the majority (83.8%) of those looking to make some sort of a switch are very to somewhat confident they can find a job with the same income and benefits as they have now.

Facing Barriers to Work

Many individuals are faced with few employment choices or less than optimal ones. The pandemic laid bare the extreme barriers many people face each day in finding, keeping and advancing in a job—from transportation challenges, lack of quality, affordable childcare, insufficient digital access, health-related limitations and disabilities, and caregiving responsibilities.

Many of these factors are due to systemic issues that are bigger than individual companies, and disproportionately impact low-income workers and people of color. While there are opportunities for employers to improve offerings to make it easier for people to find, maintain and advance in careers, public policies and broader community and economic development strategies to improve digital access, transportation, health and childcare should be pursued in earnest to help people connect to work.

Nearly one in five adults—or 407,725 people—have had difficulty finding or keeping a job in the past 12 months. This percentage is higher for workers who are young (26.6% among 18- to 30-year-olds), Black (29.3%) or parents of young children (29.1%). The top barriers to employment include: opportunities paying too low to support a family; health issues or concerns for their own health or that of their family; disabilities; lack of work experience, transportation, and childcare issues. Many workers also remain digitally disconnected or struggle to access the training and education needed to get ahead. We explore some of these barriers in more detail below.

Pay too low

By and large, employers raised wages during the pandemic, but not enough. Nearly half of all working-age adults surveyed (47.4%) cited low pay as an extreme or moderate barrier to finding and keeping employment. More than 50% of women, 18-30-year-olds, Black or multi-racial workers, and workers with children under five cited low pay as a barrier.

From 2019 to 2020, hourly wages increased at a faster rate than during the previous eight years combined, across all income levels, with the exception of the highest earners, who still saw a sizable 4% increase in wages.3 That growth slowed significantly between 2020 and 2021, and in some cases, i.e., among higher earners, wages dipped. Employers might feel like they have exhausted their options when it comes to pay, but this barrier will only become more pronounced amid rising inflation.

Health challenges and disabilities

Almost 46,000 people aren’t working or aren’t looking for work because they have health issues.

Health-related challenges are a significant barrier for Northeast Ohio’s workers. Health issues of their own, disabilities, concerns for the health of oneself or family members, and caregiving responsibilities, showed up a lot. The health and well-being of Northeast Ohio’s workforce is critical to workforce participation. While there are some things employers can do to support these workers, whether it be actively recruiting and making appropriate accommodations for individuals with disabilities, supporting workers who are caregivers with the flex time they need, or ensuring a safe work environment, the state of health care and the barriers individuals face to adequate, affordable care are systemic issues that require systemic solutions.

Other systemic barriers

The survey also revealed the impacts of systemic barriers to employment over the course of the pandemic, including lack of access to training and education, lack of access to technology, and lack of transportation.

Lack of access to training/education

Access to training and education is a significant barrier for a large part of the workforce. Here are some staggering numbers that back up this point: An estimated 481,559 people feel they don’t have the necessary education or training needed to get ahead in their job or career; 1,167,469 people are unaware of job-related training or education programs in their area; and 359,707 say it’s difficult to pursue additional training.

Digitally disconnected

Digital access is also a big hurdle to employment. An estimated 556,911 people in Northeast Ohio don’t have internet access; 310,057 only have a smartphone and no access to a computer, tablet or e-reader. Unsurprisingly, Black or multi-racial, very low-income (under $25,000/year) and very young adults (18-24) are more likely to not have access to the internet, segments of the workforce who could benefit the most from such access.

References

- Source: PBS Newshour: “U.S. job openings remain high, with nearly twice as many openings as unemployed people”

- Source: U.S. Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators for 11-county region

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics: https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm. Based on hourly wages, adjusted to 2021 dollars, of workers in the four Northeast Ohio MSAs (Akron, Cleveland, Canton, and Youngstown) over time, by percentile. All data pulled represents data from May of the corresponding year. For additional information on percentile wages, see: https://www.bls.gov/oes/oes_perc.htm

Details on an outcomes set.